Why to study Folds and Folding?

Various geological processes leave traces of their activity as rock structures. These structures can potentially serve as a source of information that is essential to interpret the history of the Earth. Establishing the relation between a process and the resulting structure is therefore important to decipher the geological history recorded in the rocks. The sensitivity of the structure on factors such as rock rheology, temperature, pressure, or water content can provide additional information about the Earth structure. Folding and folds are an example of a geological process and the resulting structures it forms. Folds contain information about rock properties and natural processes of deformation. Although, both the structure and the process have been studied intensely, the relation between folding and folds is not satisfactorily established. This is due to the fact that the folding process is not fully understood and there is a lack of methods that can accurately describe the geometry of a generic fold. Thus, the aim of my research is to advance the understanding of the folding process itself, its relation to the resulting fold structures, and its influence on the bulk properties of rocks.

Fig. Examples of natural folds with various geometries

Fig. Examples of natural folds with various geometries

on various scales.

Folding Process in Rocks

Folding of a single layer

I would like to advance the understanding of fold initiation and growth to the large amplitudes.

Folding of nodular layers and inclusion-bearing layers

Inhomogeneities in rocks can significantly affect the bulk mechanical properties that in consequence influence forming structures during deformation. Inclusions that can represent mineralogical or structural variation in the rock are the examples of such inhomogenities. In my study, I focus on the role of presence of the rigid inclusions in the layer as well as the align inclusions (e.g. nodular layers) that form a layer on rock strengthening and their influence on the folding instability.

Fig. Folded nodular layer from Oslo Area.

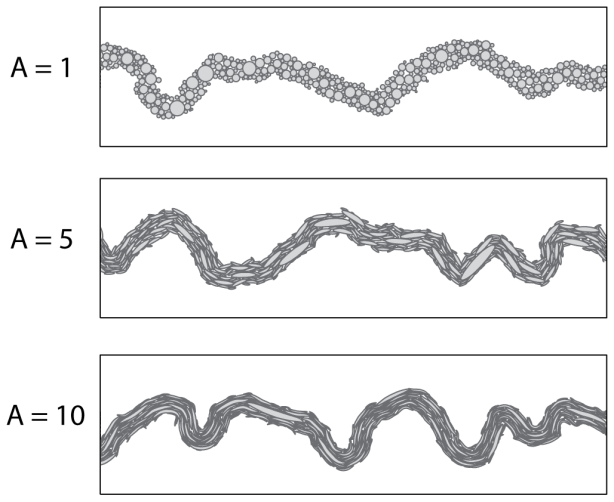

I study folded nodular layers in the field in Oslo Area (picture above), and also investigate the behaviour of such systems numerically and their sensitivity to the changes of various parameters. As an example, the picture below shows the results of three numerical models of folding of the inclusion layer where different inclusion shapes (aspect ratios – A) are used.

Fig. Numerical results showing the variation of the fold shapes for

different shapes of inclusions (here, aspect ratios of ellipses)

after 40% of shortening.

Fold Shape Analysis

An accurate description of the fold shape is important to unravel the information recorded by the rock during deformation. The purpose of this work is to identify a distinctive set of parameters that allow for an unambiguous correlation of the fold shape with the folding mechanism and a range of contributory factors.

Tectonic structures within the salt diapirs

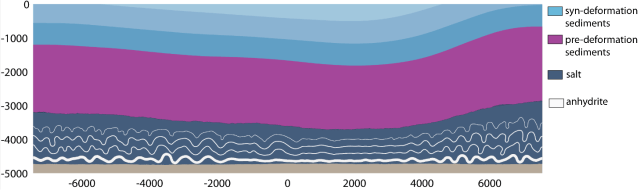

Evaporate series are composed of a range of interbedded rock types such as carbonates (calcite, dolomite), sulphates (anhydrite, gypsum), and chlorides (rock salt, potassium and magnesium salt). The presence of evaporates particularly with thick salt layers within sedimentary basins significantly influences their tectonic evolution. This is due to unique properties of salt, which cause that salt buried under sediments becomes buoyant and migrates towards the surface promoting development of diapiric structures. The intensive complex deformation that operates on the layered evaporates sequence leads to the development of a complicated diapir internal architecture. Varying material properties such as viscosity and density of different rock types in the evaporate series contribute to the complexity of the formed structures. In this studies, I want to focus on the role of mechanical stratification within the evaporate series on the evolution of the internal salt diapiric structure.

Fig. Numerical results showing internal deformation within the mechanically heterogeneous evaporate series during the initial stages of diapir formation. The deformation is accompanied by the bulk model shortening and sedimentation.